Blog & Photo Archive

Birding is about finding beauty in the everyday birds; the thrill and passion comes from the backyard species as much as it does the once-in-a-lifetime bird, as does the responsibility to protect them.

These entries are vignettes, lessons, personal reflections, and conservation efforts.

Please note that this website is best viewed on a device other than a phone.

January 2, 2025

Tristram's Starling

The starling family, Sturnidae, is a group of birds native to the old world. These birds are well known for having complex vocal capabilities and beautiful plumages. Males have shiny, glossy-black plumage with orange primaries while females and juveniles have duller, brown plumage.

Tristram’s Starlings travel in large flocks, nest on rocky cliffs, and are native to the Mediterranean Region. They are common in Southern Jordan and around the Dead Sea but rarely seen in very arid regions,. Their range is mainly in Saudi Arabia along the coast of the Red Sea and even extends further into the Southern Sinai peninsula (Egypt). They travel in large flocks in order to forage with a lower risk of predation.

Bedouins note that the Starlings enjoy feeding on fruits, especially figs, dates and olives. They also feed on ticks while stooping on camels, creating a symbiotic relationship between the two species. In Yemen and Oman, they have been reported using tools to break apart snail shells.

Although many consider starlings to be loud and annoying, I feel their beautiful songs make our everyday environment more enjoyable.

January 3, 2025

Eurasian Kestrel

As our pickup car stopped at a sight to watch the sunset over the Wadi Rum, I looked out into the distance and spotted a small falcon that I couldn't comfortably identify due to the bird being too far. As I continued to follow it, walking farther and farther from the car, I couldn't help but notice the familiarity of its features being similar to those of a Kestrel.

The Eurasian Kestrel is a small falcon with a gray head, rusty back, and a gray tail with a broad black tip in males, while females are brownish with barring. This species inhabits various environments, including urban areas like Amman, where I saw it numerous times flying over apartment buildings. Kestrels feed on rodents, small birds, and large insects and are in the falconidae family, or the falcon family.

Falcons are highly valued for hunting, symbolizing status among Bedouin tribes and representing a connection to nature in Arab culture. They are seen as faithful servants in Islam due to their ability to perform tasks and return to their master. Kestrels are often supported by farmers who build nests for them to help control rodent populations.

I walked back to the car, excitedly carrying my camera and marveling at the in-flight photo I took of the Eurasian Kestrel. I quickly showed our Bedouin driver the photo I had taken and he was also excited to see a wild raptor within the Wadi Rum.

January 7, 2025

Temminck's Lark

Out of all the birds I have observed in Jordan, the Temminck’s Lark has been one of my favorites. Their backside perfectly blends into their surrounding environment, but when they turn to face the observer, a striking black mask, throat, and distinctive ear tufts (horns) is revealed, making the bird all the more mysterious.

This species is native to the Middle East, where it is particularly abundant in Jordan. It is the third most common lark in the Azraq area and also thrives at Shaumari Wildlife Reserve. Preferring sandy or stony desert plains and low hills, the desert lark breeds on the ground. It forages food in small groups or pairs and has an engaging social dynamic. Males exhibit a more pronounced head pattern than females.

Although the lark’s conservation status is considered to be of least concern according to the IUCN, they are locally declining in population due to habitat loss fueled by changes in land use and climate change. Their specific habitat requirements of semi-desert rocky and low altitude environments makes habitat loss all the more dire.

Temminck’s Larks also have a crucial role in the ecosystem by feeding on seeds and insects; these population changes could affect the food chain and general health of the ecosystem and biodiversity of the area. Therefore, places like the Shaumari Wildlife Reserve are crucial for protecting the Temminck's wild population and their habitat.

January 10, 2025

Great Grey Shrike

When it comes to courtship displays, shrikes differ from most other birds. Most bird species choose their mates based on the quality of their plumage or song while shrikes judge each other based on the food resources they possess.

Shrikes, nicknamed the “Butcherbird”, are carnivorous passerines that impale their prey before consumption. The reason behind this is simple: unlike raptors, shrikes lack a crop or a pouch-like enlargement that allows raptors to temporarily store food before digestion. Shrikes cannot ingest large prey and must manually impale and tear apart the meat using twigs, thorns, or barbed wires.

Instead of disregarding poisonous invertebrates while hunting, shrikes impale their poisonous prey and leave them cashed within their territory for three to five days, allowing their toxicity to slowly degrade. Male shrikes often leave prey impaled on different sites to attract their mates, and Great Grey Shrikes leave their prey impaled for several days to weeks. There can be up to ten to fifteen food stores at any given time in a shrike’s territory

Unlike females who store their prey underground or in bushes, hidden from other predators, males display their prey on top of barbed wire fences and acacia trees to advertise their hunting capabilities to a potential mate. Males store their food for up to multiple weeks while females store their food for only a couple days before eating. An abundance of food found within a male’s territory highlights his ability to protect his food source. This behavior is especially prevalent during the breeding season when males are attracting females.

As I was on a drive to visit the Dead Sea, I saw a Great Grey Shrike perched elegantly on an acacia tree keeping watch for potential prey. These birds were especially abundant while I descended from Mount Nebo to the Dead Sea. The scarce vegetation and numerous perches made it a perfect habitat for Great Grey Shrikes. As I leaped out of the car to photograph the Great Grey Shrike, I couldn't help but notice how elegantly perched the bird was, patiently overlooking the area in search of potential prey.

January 10, 2025

European Stonechat

The European Stonechat is a curious little bird of the open country. It is often found perched atop bushes and fences, dropping to the ground to catch insects before flying back up to perch. Couples will guard designated territories by flicking their wings and tail feathers before flying back to where it was last perched. I have always appreciated aerial insectivores, and enjoy watching their behavior of continuously flying back up and down from its perch.

I observed this bird twice and was struck by the male’s distinctive blackish head, set off by a big white patch on the sides of neck and brightly colored rufous breast. This species migrates into the Levant legion during its nonbreeding months and can be seen in Eastern Jordan.

February 27, 2025

Palestine Sunbird

When I first arrived in Amman, Jordan as an American exchange student, I was excited to explore bird life in the Middle East. The Palestine sunbird was a bird that particularly intrigued me. I knew that the Palestine Sunbird is the only native sunbird in Jordan, and I later discovered that this sunbird was most abundant in Amman.

Sunbirds, like their New World counterparts, hummingbirds, are nectar-feeders. I often observed male sunbirds, their metallic blue and purple plumage glistening underneath the sun, either singing or defending their territory. The Palestine Sunbird has a long, curved bill and split tongue that aids in the extraction of nectar. Males have a rich, complex song that differs from other sunbirds.

Living in a city made challenging to connect to connect with nature, I found comfort in nature by watching a male sunbird perched in front of my window, singing his beautiful metallic whistling song.

The Palestine Sunbird is a symbol of hope, freedom, and resilience and is widely recognized throughout the Levant as being the national bird of Palestine. I often saw the Palestine Sunbird depicted in murals painted alongside maps and keys, depicting loss yet also conveying a message of hope for the future.

February 27, 2025

Hooded Crow

The Hooded Crow is the most common crow species in Jordan and is very common in urban areas. I often saw this bird on walks around my host city, Amman.

The Hooded Crow forages most of its food and its durable bill allows it to have a diverse, omnivorous diet. Crows are aggressive to larger birds such as intruding raptors. In the Quran, the Crow is mentioned in the story of Cain and Abel (قابيل, هابي). When Cain killed his brother, Abel, Allah sent a Crow to teach him how to properly bury the body. The Crow teaches Cain how to take responsibility for killing his brother by providing a proper burial.

The Hooded Crow, a familiar sight in Amman, showcases its adaptability and survival skills through its successful foraging and its aggressive nature. The crow's story in the Quran, where the crow teaches the value of a proper burial, exemplifies the crow’s intelligence and its association with taking responsibility.

April 1, 2025

Sinai Rosefinch

The Sinai rosefinch is the national bird of Jordan. The male is on the Jordanian one dinar bill. The Sinai Rosefinch was chosen to be the national bird due to the male’s pale pink plumage on its face and breast that mimics the stone of Petra. This species lives in deep desert canyons in Southern Jordan (Ma’an, Al’Aqaba) and is commonly seen in Jordan's famous desert, the Wadi Rum.

Wadi Rum is known as the desert where the movies Dune and Martian were filmed, and the desert has been popularized due to the picturesque landscape. However, during my visit to Wadi Rum, I most appreciated watching the Sinai Rosefinch and learning about how it and other desert birds have evolved to camouflage themselves in this unforgiving habitat. The male's pink plumage and female’s tan plumage allow groups of Sinai rosefinch to stay hidden from predators within the sandstone formations.

The Bedouin people, a Jordanian tribe that lives in Southern Jordan, have begun to make water stations for birds like the Sinai Rosefinch to help increase their local population. Many Arab nations struggle with illegal trafficking and hunting of birds and seeing this new effort done by locals to help conserve birds makes me more hopeful about conservation efforts in Jordan.

April 18, 2025

Arabian Green Bee-eater

The Arabian Green Bee-eater is the only Bee-eater species endemic to the Middle East. This species is a resident in southwestern Jordan, in the lowlands along Wadi Araba and the Dead Sea margins. It has expanded north to parts of the Jordan Valley north of the Dead Sea and adjacent wadis in the last few decades. When discovered by Western explorers in the 1860s, this gorgeous species was believed to be the same as the tropical Asian Green Bee-eater and African Green Bee-eater. Thus, for the next 150 years, these three species were lumped into the Green Bee-eater with a range that extended from North Africa all the way into Asia. With recent morphological analysis, the three species were split into the Asian Green Bee-eater, African Green Bee-eater, and the Arabian Green Bee-eater. The Arabian Bee-eater is slightly larger than these two species and differs in plumage, having a distinctive azure-blue forehead, cerulean blue throat, and blue-green belly.

I first saw this species in early January in the Dead Sea. I had longed to find this Bee-eater and knew that its range extended into Jordan. I had been living in Jordan for more than four months and made a trip to the Dead Sea with my mother who was visiting over winter break. As we drove into our hotel I noticed an oasis of acacias, habitat which could host avian diversity. With my prior knowledge on the species I knew that the Arabian Green Bee-eater is known to prefer arid habitats with scarce vegetation and occurred in Western Jordan. As soon as we parked, I ran out of the car with my mother trailing behind me. In my hands I was carrying a field guide and binoculars. I was overwhelmed by so much bird activity nestled in a one acre area. As soon as I started my eBird checklist, my mother alerted me that she had spotted two Bee-eaters perched on a wire, and to my excitement it was the Arabian Green Bee-eater!

In April, I visited Western Jordan again and although not on a birding trip, I still brought my camera and binoculars in case I saw a new species. I was in Bethany to see the sight of Jesus’s baptism and as I was walking back to the car, I saw the silhouette of a bird flying over my head. I looked over to where the bird had landed and there were two Arabian Green Bee-eaters. I rushed to my friend, Aeiris, alerting her that one of my favorite Jordanian birds was perched four meters away from us! I ambled closer to the birds and began snapping photos.

The Arabian Green Bee-eater is loved by most birders and photographers for its elegant beauty and dramatic aerial foraging bouts. This species feeds on flying insects, hence the name bee-eater, and can detect their prey from up to 70-100 meters away. Not only does this species consume insects, but it has reportedly been found consuming grains of sand to aid with digestion. Bee-eaters have physiological immunity to bee venom that allows them to consume bees.

These birds are usually observed as pairs or small flocks (family parties) and unlike their Asian and African counterparts, Arabian Bee-Eaters practice cooperative breeding , nesting in built holes in sand banks. Ideally, pairs have a territory large enough to provide a sustainable supply of flying insects, but small enough for the pair to be able to defend it.

In conclusion, it is fascinating learning about dramatic behavioral differences in very similar species. The Middle East is often overlooked for not having diverse or interesting avifauna but the Arabian Green Bee-eater is truly a hidden gem found only in this region of the world. I am so grateful I had the opportunity to travel to Western Jordan and be able to photograph and appreciate this species.

May 20, 2025

Graceful Prinia

The Graceful Prinia is an oftenoverlooked bird due to its small size and overall dull plumage. However this tiny bird, in my opinion, is incredibly cute! It sings in a high-pitched trill and is always hastily moving around bushes and trees, wagging its tail from side to side.

Males take up to four days to build a closed nest nestled between a forked low branch. Once the structure of the nest is built the female cares for the lining, perfecting the nest before she lays her eggs. The newborn hatchlings weigh 0.9 grams and reach a weight of 7 grams within their first 9 days! This illustrates how nutritious insects can be in a bird's diet, allowing a hatchling to grow 44% of its body weight each day.

I would often observe this species at the Zahran Park in Amman. The abundance of bushes and trees at the park made it a perfect habitat for many birds, especially the Graceful Prinia.

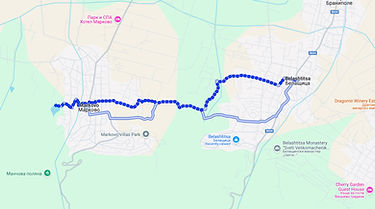

About 5.5 km to walk, though it took us 3.5 hours to get there!

2025

Eurasian Hoopoe

Towards the latter half of my exchange experience in Jordan, I began accompanying my friend Adelina—an avid birder—on her birding-related excursions around the capital Amman. Curious to understand her enthusiasm for feathered vertebrates and equally eager to get out of the house, I would point to various birds and wait for the ensuing commentary (e.g. “What is that?” “A Palestinian Sunbird.” “What is it doing?”, etc.) as we explored our neighborhood, parks, and historical landmarks. It felt as though I was let in on this well-guarded secret—sneaking into iron-wrought gardens to spot a fledgling sunbird, and then ungracefully scampering away after the homeowners had come out to see what these two suspicious figures with a camera and binoculars were doing in their yard; traipsing over weeds and under low-hanging palms to chase an European Honey-buzzard, before unexpectedly spotting a Syrian Woodpecker (blink, and it’s gone!); laughing at The Big Year, teary, after a rough day (in which, if you must know, I had ripped my third consecutive pair of pants). It felt as though I had been given a ticket to happiness and told to look for it—and here it was, everywhere around us! Flying, chirping, warbling, trilling…

In this pursuit of happiness, I soon discovered that birds, unlike men, are not created equal (forgive me, Founding Fathers). There was one bird I wanted to see above all—the Eurasian Hoopoe. Unmistakable in its likeness, the hoopoe has a bright orange body, black-tipped mohawk, zebra-striped wings, and a long, downward-curved bill which it uses to probe the ground searching for spiders and insects. You might also spot it sunbathing in all its glory, with spread wings and an uptilted head. Its unusually flamboyant appearance (second to no other, except maybe the Ruff) made frequent appearances in my sketchbook; its elusive nature (though seemingly everyone else saw one) only intensified my desire to spot it. I was reminded of my many days spent searching for shinies in Pokémon, except now I had a real-world equivalent to fixate on. In any case, as our program drew to a close, I became too busy with projects and last-minute visits to go out hunting for one. The thought of finding a hoopoe was nestled in the recesses of my mind, then preoccupied with going back home to the States and then abroad again to visit family.

Upon arriving in Bulgaria, greeted by its oppressive, sweltering summer heat, green mountains, and the familiar sight of stork nests teetering on lampposts, I vowed to get out and bird as much as I could. Little did I know, identifying various birds without Adelina and rising early enough to beat the midday heat was a challenge on its own! Still, with plenty of eBird photo quizzes, morning alarms, and applications of bug spray, I managed to get out of the house—this time equipped with my own gear (that is, Soviet-era binoculars my grandfather lent me, my mother’s old Nikon D5000 with a newly-equipped 70-300mm lens, the Merlin Bird ID app, and the few pages I photographed from the library-exclusive Birds of the Balkan Peninsula field guide).

One morning, my cousin Ina (a welcome participant in my morning walks) and I rose at 6:20 to hike to a nearby village’s reservoir. Armed with a hiking stick, three bottles of water, and stale солети (pretzel sticks), we set out on our journey. Passing through Belashtitsa’s own reservoir, we were lucky enough to see some new species—like the Black-headed Bunting—and hear a few others, before venturing further up into the mountains.

After swallowing a fly and startling a grass snake, though, I was ready to turn back. Ina, sensing my unease, gently patted my hand and took it in hers. “We could go back home,” she offered, “or we could continue. No matter what, at least we got to do something new together!” She was right. This too was part of the adventure, and as much as I had been spooked, when else could I feel the morning wind cool our foreheads as we skipped and laughed along grassy trails? “Best to make the most of the moment, ah?” She nodded in agreement. And with Fetty Wap on full blast to calm my nerves, we trudged forward.

Though our challenges did not stop there, like being stalked by an all-black, pregnant rottweiler right as I was trying to snap a picture of a nearby warbling Greater Whitethroat—oh, the horror!—we slowly but surely grew closer to our final destination. At one point, I could have sworn I saw the unmistakable—the hoopoe—or had I…? We had stopped to catch our breath in some grassy clearing, when we spotted two birds in flight, a flash of black, white, orange, and a pair of oddly-shaped heads.

Was it? Or was it not? Hopeful, we continued on, nearly at the reservoir. At this point, the sun had unfurled its rays, which now draped on our backs like tendrils of heat, leaving pools of sweat in their wake. Apart from a huge flock of Western House-Martins, there wasn’t much else, and we were ready to return home, having called our grandfather to pick us up.

Then, right as we turned our backs to leave, I heard it.

Hoo poo poo….

Hoo poo poo…

Its song echoing over the reservoir.

Crazed, I spun around, waiting for it to sing again. Inhale. Exhale. Inhale. Hoo poo poo…

If only you saw how I fell to my knees! And then, nearly tripping myself, how I ran to shake Ina’s shoulders, squealing hoo poo poo all the while!

❖ ❖ ❖

I find that birding invokes the same feelings of wonder and thrill I felt in my childhood, like when my mom and I would discover pockets of wild blueberries along forest trails, or sight the peaks of Bulgaria’s tallest mountains after hours and hours of walking. Through effort and a sprinkling of luck, familiar landscapes are transformed into treasure chests of birds and woodland creatures beckoning you to come closer, to see them, to hear them. It inspires a certain kind of appreciation for all the little things life has to offer if one takes the time to stop and observe; to marvel, perhaps, at dozens of egrets and herons flying around you, or find amusement in the way a wagtail bobs its tail up and down.

When birding, I feel slower, quieter, enmeshed in our world, paused between the burden of expectations and responsibilities and reality—alive in the simplest of ways. I pause to take it all in. And once the moment fades, I find myself wondering: what will I see next?